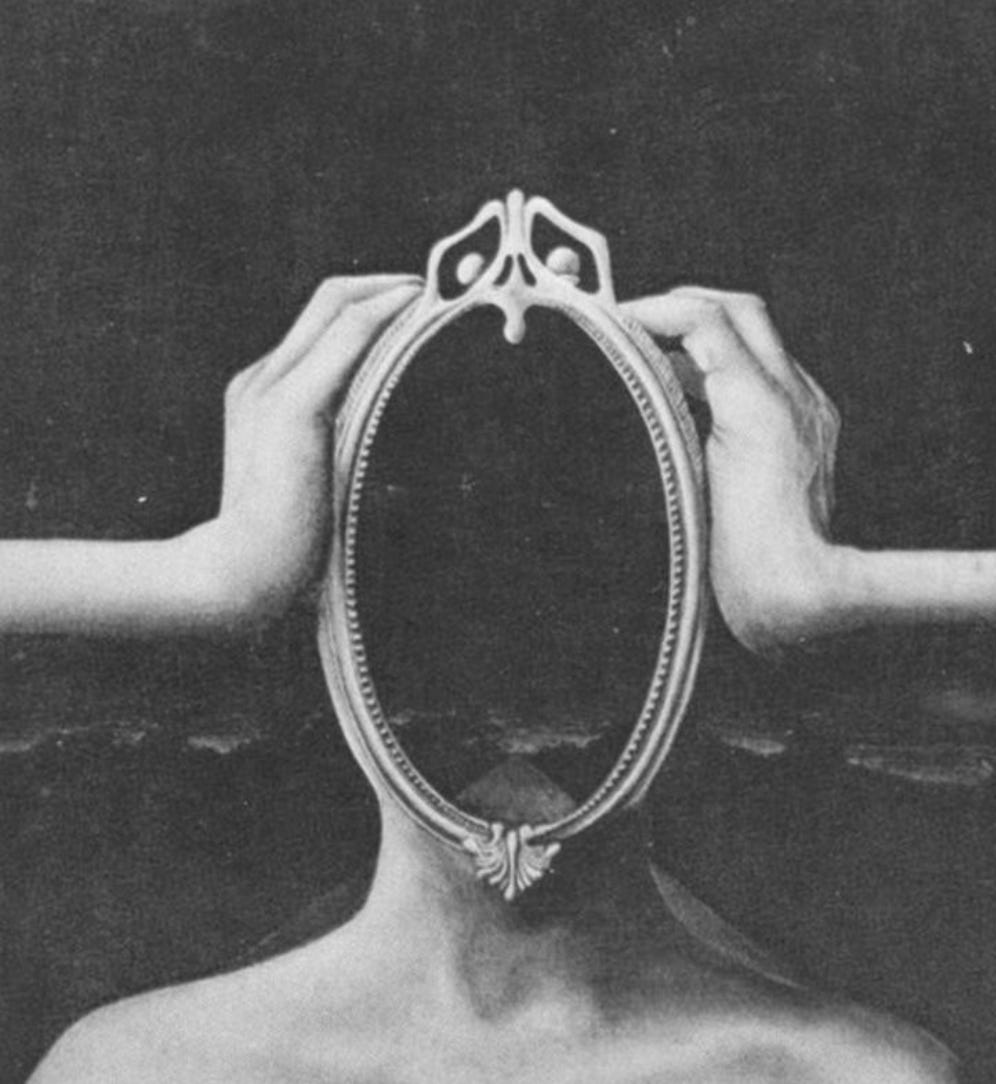

Negative Identity

Negative identity is the part of ourselves that crystallises what our parents reject, the negativity that we perceived in them that then becomes a compass for us.

Dear Readers,

If you believe in the value of quality writing and the importance of creating a space for curiosity, critical thought, and meaningful dialogue, your subscription makes that possible.

Join as a paid subscriber to help build a community that values ideas, reflection, and the exploration of what it means to be human.

In a previous Substack, I commented on the crisis in child and adolescent mental health, and reviewed some of the explanations and arguments around this. One striking feature of the way in which the debate has changed over the years is that we no longer speak of ‘the delinquent’ or ‘the problem child’, but prefer to use the language of conditions and categories: ADHD, ASD, CD etc. This is clearly much less stigmatising, moving blame and fault away from the child and no longer seeing them as responsible for their difficulties.

This redrafting, although it has its issues and complexities, offers a much more humane approach and can open the door to greater understanding and care. In some cases, however, the categories we use can obscure underlying dynamics which revolve, ironically, around exactly the question of identity that the currency of mental health labels seems to destigmatise. Labels confer an identity, and one of the central dilemmas of adolescence is to test and create identities, compass points with which to navigate the world and to provide a positioning within one’s peer group.

Some people gravitate towards labels that might seem rigid – think of the old divisions between punks, mods, rockers - while others prefer to move away from labels altogether, rejecting systematically any attempt to define them. A label that names the very tendency to reject labels is thus very welcome for some – ‘non-binary’, for example. But there are also individual, unconscious labels that circulate in families and that are very rarely visible to the outsider. And it is precisely these unseen, unspoken labels that can affect adolescents in the most dramatic ways.

If a child feels unrecognised, unheard - perhaps unloved - how can they find an identity growing up in an environment that ignores or negates them? Sometimes, the family is loving, yet the child senses duplicity: they are pushed towards an ideal that does not ring true: the well-behaved perfect princess or prince, the overachieving pupil, the sports champion, the prodigy. In this atmosphere of alienation, the youngster brings into play the most basic weapon a human being has: truth.

In the absence of any authentic recognition, and in an atmosphere of artificial ideals being foisted onto them, the child turns not to what she or he is supposed to be than to what they are least supposed to be, identifying with elements presented by the family as the most undesirable or dangerous, but crucially, as Erik Erikson pointed out, as most real. This is what he called ‘negative identity’.

If a sibling has died and the parent is unable to attach to subsequent children the devotion bestowed on the lost child’s memory, they in turn might seek their own identity in the image of the sibling. It is more true, more real, than the superficial attention and interest they might have received themselves. Or if a parent repeatedly evokes some ne’er do well relative, or rejected troubled soul, this might act as a magnet for the child, as what it offers is a more solid anchor than what they perceive as false ideals. There is more truth in the rejection of this person than in the exhortations to be something that they themselves are not.

Just as infants and children forge their subjectivity through saying No to their caregivers, showing their difference and autonomy through small acts of refusal, here there is an even bigger No, as if the outsider or rejected figure is a living incarnation of refusal, of difference. As Erikson put it, negative identity can be “dictated by the necessity of finding and defending a niche of one’s own against the excessive ideals either demanded by morbidly ambitious parents or seemingly already realised by actually superior ones: in both cases, the parents’ weaknesses and unexpressed wishes are recognised by the child with catastrophic clarity”.

Rather than struggling to find reality in roles which are, for whatever reason, unattainable, the child’s radar goes to the truth which the parents only half-say: the lost child, the criminal relative, the lonely rejected uncle or aunt…The parents’ dismissal or rejection of these figures carries more truth for the child than the exhortations to be happy, to be a great student, to succeed, to achieve…and so they may choose a comparable place, a negative identity. Instead of a doctor, a lawyer or a movie star, they choose a symbol of failure, estrangement or even crime.

Added to this is the fact that a parent may respond selectively to those traits in their child that remind them of the rejected figure. A parent whose sibling disintegrated into alcoholism or crime may respond especially to those traits in their child that point to a repetition of the sibling’s fate. The negative identity here may seem more real than all their attempts to be good, a counterpoint to the failure of their effort to get everything right, to be perfect. It is easier, after all, to fail than to succeed, and all the more so if failure has more truth to it than success.

Negative identity is the part of ourselves that crystallises what our parents reject, the negativity that we perceived in them that then becomes a compass for us. It’s our appropriation of the limit point of parental repudiation.

When we encounter troubled adolescents, this may well be part of the picture in some cases. Recognising it is important, as it shows how what might seem to be a symptom or a disorder is in fact a kind of solution, the creation of an identity even if this is a negative one, the opposite of the surface ideals of a family and of society more generally.

I think what's missing here, to express it, is Lacan's single trait (trait unaire), through which the child inscribes itself by introducing itself with the set - similar to how humanity does with the notch. And isn't it much more significant how the category models of diseases specifically give space to the trait (that is, the form) of the notch? By this, I mean that the child, at least in the assumption of a subject, does not represent itself for itself or other subjects, but precisely as a signifier in relation to other signifiers. It takes a place where it wants to see itself represented in this illness, and desire is precisely the desire of the Other, which means that the needs and wishes are anticipated based on the clinical picture. In this sense, the illness shows us not only what the child is suffering from, but also what it should desire, what it should claim, and how the child must do it.

Thank you for your text.

As ever this is a very interesting piece. For me though I am yet to find a genuinely non pathologising psychoanalytic understanding for autism. Rather than just being a new label for an old delinquency, the emerging science around neurodivergent brains is filling this space for me. But this is a slow process.